When did you first get involved in the Nuclear Freeze Campaign and what motivated you to get involved?

I remember the exact moment I became involved in Nuclear Freeze Campaign. In the spring of 1982 I saw a photo on the front page of the Grand Rapids Press reporting on an antinuclear march that took place in downtown Grand Rapids. Seventeen-year-old Louie Villaire, was carrying a nuclear “bomb” and I thought “finally, someone is doing something about the insanity of the arms race”. The march through downtown was one of the first in a series of events that would draw me into the local discussion about the nuclear arms race that was out of control and endangering the entire planet. Within a week I became involved with the Ground Zero Project, an effort to educate people about the dangers of nuclear weapons.

What kinds of activities were you involved in and what kind of training was there to assist to in the work that you were doing?

That article included an announcement of a meeting for people interested in getting involved in the Ground Zero Project. The Project was sponsored by a local Physicians for Social Responsibility group and the meeting was held at Saint Mary’s Hospital. Attending that meeting was the beginning of my involvement in local and state political issues related to stopping the arms race. The Ground Zero Week Project had one or two paid staff. Bruce Triemstra was the primary coordinator and Margi Derks worked with him to maintain an office and recruit, train and manage volunteers and coordinate the educational events.

I was one of those volunteers and worked hard to learn about the issues and also hit the streets of Grand Rapids gathering petition signatures and distributing information on the arms race. I also worked on some of the events.

The first event I worked on was a media tour of places in Grand Rapids that would suffer in a nuclear “hit”. I was responsible for producing large posters with the Ground Zero logo for 3-5 locations. This was in 1982 before computerized graphics were easily produced and available quickly and cheaply. I bought the supplies and worked all night long to design and construct the posters. I did not like the national Ground Zero logo so I redesigned it so it looked like a circular target with a large, pointed arrow aimed at the center. The official logo was similar, but to me it looked weirdly like Satan’s tail. My suggestion to redo the logo was not supported, but I did it anyway.

At 6:30 a.m. the posters were done and I drove around and installed them at predetermined places. One was on the Calvin College campus, another on the Monroe Mall, downtown. The posters described how many people would be killed in a nuclear strike and other scary facts

There was no in-depth training for volunteers because there was no time for it. I learned by osmosis. I attended dozens of meetings and listened and read as much as I could to develop a base of knowledge on the issue. Every activity from organizing tactics to discussions/arguments about actions to take was an opportunity to learn. I sometimes felt unprepared and not knowledgeable, but the organizers and other volunteers were supportive, kind and inclusive. I came to feel that I was a contributor and helpful to group goals. There were a lot of college students who volunteered hundreds of hours that spring and summer. Diane Stoneman, Sue Hartman and Barb Boylan are three that I got to know well. I admired their grasp of the issues and their dedication to making sure decision-making was a joint process and based on consensus.

One part of political and community organizing that I learned was that it had to be fun. The work was so intense, there was too much to do, very little money to do it, multiple personalities, a need to communicate with dozens if not hundreds of people state-wide, and of course there was political backlash to deal with. Fun was essential or we would not have survived to reach the goal of getting 300,000 people to sign petitions to get the issue of a nuclear freeze on the Michigan ballot and get it passed, despite the opposition of the political establishment in the Reagan era.

There was so much to do that Bruce and Margi just piled on jobs and anyone in the office was fair game. We were located in the White and White Medical building on Sheldon Avenue SE across the street from the YWCA building where the Nuclear Weapons Freeze Campaign had opened an office. They were two different groups sharing similar goals. I eventually landed with the Freeze campaign when the Ground Zero Project was completed.

After the media tour I worked at calling hundreds for people who had indicated interest in the issue and asked them to take petitions and get their friends, neighbors, church groups to sign them. I also recruited people to petition at grocery stores, at events like Tulip time in Holland and at the River Bank Run. You could hardly walk downtown without meeting up with a petitioner asking you to sign.

Recruiting volunteers is an art that I learned by doing. The expectation in the campaign was that if something needed to be done the staff would grab the first person that walked in the door that morning to do it. When I started volunteering at the Freeze office I was asked to write a news release. Mark Kane, the Director of the local Freeze Campaign, handed me the featured speaker’s curriculum vitae. I was to use this as a guide for describing the speaker’s credentials and accomplishments as part of a media release. I did not want to admit that I did not know the first thing about drafting an announcement that would attract media to our news conference.

Mark gave me a copy of an old news release and I spent the entire day agonizing over a one page document. That done, it got worse. Mark asked me to coordinate and speak at a news conference announcing a now-forgotten event. What I have not forgotten is my quavering voice and wanting to melt into the floor of the conference room at the YWCA as I mangled the information I was trying to present. I was more than relieved to see on the evening news that my part of the event was “talked over” by a reporter who presented the facts more coherently.

Was there a central organization working on this campaign or was it a network of groups?

There was a state-wide Freeze Campaign, along with many community Freeze groups but I was only peripherally aware of them at that time. Our local effort was part of a loose coalition small groups in Michigan. Mark identified many of the groups in his interview.

What sorts of tactics were you using to inform/engage people about the nuclear freeze campaign? (Describe or share a story)

We leafleted on the Monroe Mall downtown on a daily basis. We also petitioned at events like Tulip Time in Holland, outside of grocery stores, and at any event that would draw a crowd. We organized candidate forums, a speaker’s bureau, and worked with the local World Affairs Council to bring in well known speakers to Grand Rapids. I was asked to speak to a women’s group in East Grand Rapids because no one else could go that night. I did not want to do it at all because I feared that the questions would expose my lack of a deep understanding of the international political underpinnings of the arms race and of all the possible consequences of freezing the arms race. The discussion went well because I did not present myself as an expert but instead as another woman trying to keep the world safe for her family and friends.

So though we are not experts we know the difference between right and wrong and we can be deeply suspicious of those who believe we have no place in decision-making. That attitude lead to excursions to Walled Lake, Michigan, K.I. Sawyer Air Force Base where I was arrested for trespassing, and finally to joining thousands of activists at the 1983 March for Peace in New York City.

During the late l980s there were weekly protests on the issue of U.S. intervention in Central America. That was during the time that Ollie North was engaged in criminal activities that supported repressive regimes in Central America. After the picketing we often had potluck dinners where discussion of other “actions” would take place. One night Sheldon Herman, Nate Butler, Kate Byrne, Eddie Gersh, and I sat in my kitchen on Logan Street and one thing led to another and we made up a poster that looked like scrawled graffiti. The “Stop the Invasion” poster became a Campaign of the same name. The Stop the in Campaign (of Central America by the U.S.) STIC was born. We hatched a plan for street theater that we realized later could have resulted in one or more of us being shot. Four or five of us were posted in various parts of the city. Nate Butler was out at the Kalamazoo Meijer, Liz Oppewal was in a County Commission meeting, Theresa Wylie was in the GRCC Student Commons and I was standing in front of the Amway Grand Plaza Hotel. Each of us was kidnapped by a group of our cohorts dressed green fatigues and black berets or with scarves covering their faces. They represented government troops in Central America. The screeched to a stop and piled out of an old VW van, we had  borrowed, grabbed the “victim”, shoved them into the van and tore off. The “troops” had cardboard weapons cut-outs of cardboard. After our kidnappings other members of our group passed out leaflets explaining the terror of living in El Salvador where kidnappings and disappearances occurred daily. Though we had alerted the Grand Rapids Police Department Community Affairs Unit in advance, they did not anticipate a problem until they got calls to 911 from people who thought the events were real. Afterwards we realized that one of us or others could have been killed. I personally regret that some were really frightened. Our message was pure but our delivery was not as well thought out.

borrowed, grabbed the “victim”, shoved them into the van and tore off. The “troops” had cardboard weapons cut-outs of cardboard. After our kidnappings other members of our group passed out leaflets explaining the terror of living in El Salvador where kidnappings and disappearances occurred daily. Though we had alerted the Grand Rapids Police Department Community Affairs Unit in advance, they did not anticipate a problem until they got calls to 911 from people who thought the events were real. Afterwards we realized that one of us or others could have been killed. I personally regret that some were really frightened. Our message was pure but our delivery was not as well thought out.

Another STIC action was a planned sit-in at the Gerald R. Ford Federal Building in the office of U.S. Representative Paul Henry. We had announced the plan the day before and the “Feds” were ready for us. There were fully armed U.S. marshals standing guard at all entrances to the building. Only staff was allowed inside. A group of about 10 or twelve gathered at the Calder Plaza next door and milled around for a while with our picket signs and then left using the stairway down to the underground parking lot.

One of our members had gone out on reconnaissance the night before to find a way inside the Federal building. She located an underground tunnel from the parking ramp to the building . The next day she led us down the steps, through the tunnel under the building and up a staircase to the office of the Representative Henry. You can imagine the reaction when our sleuth, Janet Mumaw, let the marshals know we had entered the office while they stood guard at the doors.

After an hour or two sitting-in at Rep. Henry’s office we were told to leave or we would be arrested. Some left but two of us stayed. Jeff Smith was one and I was the other. It was after 5:00 p.m. and the office staff and marshals wanted to go home. They called the Grand Rapids Police Department to come and pick us up and take us to the Kent County Jail. GRPD Lt. Victor Gillis told them he would not send out officers to do what the U.S. Marshall could do themselves. The marshals came back to the closet where they had stored Jeff and me and told us we could just leave. But we would not leave. They closed the door again and we could hear bits of conversation. After a short while conferring the door opened again and we were grabbed by the arms. Both Jeff and I fell to the floor, limp as rag dolls. They were terribly irritated and used several methods to “encourage” us to get up and walk but we deferred. They ended up dragging both of us out of the office, down the hall, into the elevator, through the lobby and out the doors of the building. One of the Marshals was kind enough to collect the lipstick and change that fell from my pocket and hand it to me before locking the doors. It was a rather ignominious end to the event but it got our message out to a few more Federal officials.

Did you build any lasting friendships based on your organizing work?

I did make many friends from the Freeze Campaign and the other organizing efforts afterward. Some who were and continue to be like an expansion of family even after these many years. But even those who I have lost touch with are still part of an experience that shaped the last half of my life and I think of them most fondly.

How did your involvement in the nuclear freeze movement impact your life after that campaign was over?

During the Freeze Campaign I became aware of other issues that the Institute for Global Education (IGE) was working on. There were two other “working groups” beside those of us focused on the issue of nuclear weapons. The Central America group was educating us on U. S. military intervention and indigenous movements there. The South Africa group worked (successfully) to get the Grand Rapids City Commission to pull city funds from companies doing business with South Africa, and less successfully to stop the local sale of Krugerands through a local jeweler, Randy Disselkon. This description barely addresses the accomplishments of the IGE groups.

Another impact that my involvement has had is that I have never entirely trusted experts or authorities since then. Kate Byrne, an old friend and activist told me that “We are the experts, not them.” I thought she was crazy but I came to believe it.” In my thirty years as a neighborhood organizer I have learned to listen to those who are forced to live with the decisions of so-called experts. I believe we can live with our own decisions, even if not perfect, more comfortably than those of experts who we are told know what’s best for us.

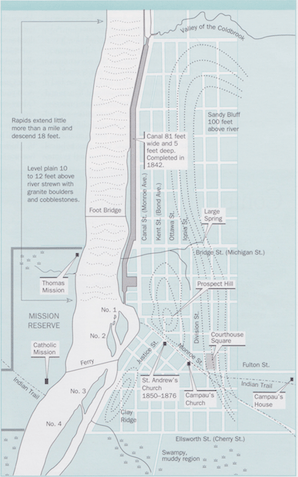

A personal example would be the destruction of the northwest side of Grand Rapids. I lived on Second Street and Lexington NW in the early 1960s and watched from my bedroom window as our neighbors across Second Street moved out and their homes were demolished. Once the freeway was built we could not get to Zamiara’s Meat Market, Saint Adelbert’s Church, or neighbors on the other side of the freeway without adding three blocks to the walk, so we just stopped going there.

Our neighborhood existed only in memory after the freeway came through. In the late 1990s there was showing of a documentary prepared by Father Dennis Morrow called Under the Freeway that explored and exposed the political maneuvering and secret plans that the political and powerful used to tear up the west side while leaving other areas of the city relatively untouched. The names are still familiar in our community.

Even after 40 years, Westsider’s and their now-grown children turned up for that presentation in such large numbers that the event was moved from the Media Center at the West Side Library to the gymnasium at Saint James School next door. There, neighbors of the past intently watched the screen as they once again saw their old neighborhood, its homes and factories and businesses before they were wiped out by bulldozers. One older man yelled out, “I delivered mail there for 40 years,” as he saw slides of homes hit with wrecking balls. Over and over people cried out memories in the dark room and the rest of us understood. Over four decades we still mourned the loss of the old West Side.

Why is it important for people to know about this local history?

Knowing about our local history helps us to understand some of the dynamics of how decisions get made and who makes them and why. Take for example how the highway impact the westside.

The decision to run the expressway through our Westside neighborhood had economic and social impacts on those of us who lived there. We went from a mostly residential area with neighbors and relatives very close by, to a neighborhood cut in half. When it was finished, the freeway rose high, like the Great Wall of China, over the rooftops of the homes left behind.

Hundreds of people just disappeared from our lives. My Aunt Vern Wittkowski was one of them. She and her son Karl, lived kitty-corner across the intersection from us. They disappeared from our lives when the expressway “took her house”. Our neighborhood, a comfortable if not particularly desirable area of the city, began to lose value as a place to live due to its location “under the freeway.” Owners were replaced by landlords and homes began to deteriorate.

My mother would have moved too, but the company that wanted to expand into the residential area of the neighborhood offered less for her house than she thought was fair. Years later she was forced to take an even lower offer much to her chagrin. Her negotiating skills were pretty good but Mr. Terry, of Miller Metal Products, got the better of her in the 1970s. That always irked her. At the end our house was the only one left on the block and it was surrounded by the walls of the factory.

Our neighborhood, and others on the west side, was sacrificed to “get something moving” in a distressed downtown area, according to a June, 2014 Mlive series on Urban Renewal, by Garret Ellison.

“In 1953, the state approved plans to build U.S. 131 though Grand Rapids, running the expressway west of the Grand River and avoiding the downtown business district. The new highway also helped facilitate the suburban growth. In no small way, the state and federal highway system became a driving force behind the desire to get something moving downtown.”

Our history tells us to speak up and current events motivate us to act up. Having access to the truth about local history fosters a certain attitude of suspicion and questioning in those of us who lived with the decisions made for us. With increased access to information about past injustice we are able to be more aware of the relationship between power, money and local and state political decisions.

Over the years shared decision-making and transparency have become part of our local political scene and citizens are called upon to participate in large group exercises that result in thick plans detailing priorities and action steps on local issues. I have been part of these groups and have read a few of the resulting documents. I end up irritated at what seems to be pandering, with long and detailed plans that don’t lead to significant change.

Without powerful local and national movements like Black Lives Matter (BLM), racial injustice would have continued unabated. BLK has exposed an incredibly ugly underside of policing and incarceration in the United States. None of this was news. It had been spoken of for generations. Because of BLM outrage, anger and action we finally have hope that real change might take place.

I love that BLM has broadened its focus to demand justice for Black transgendered people and has challenged the rest of us to act up too. That is a bold and brave step and I applaud the group for the courage to challenge their own membership. I am not sure of my place in that movement but I want to be there on some level.

So, if local history has any importance at all, it is that it exposes injustice, fosters conflict and supports the activism of those seeking justice.